Accessing these databases might be easier than you would think. Increasingly, public libraries are buying into the programs. You can get a free library card if you live nearby, and if you don't, you can often pay a pretty reasonoable fee to become a member. For example, I spent $20 for a year-long membership to the Mid-Continent Public Libary system over the river in Missouri. Between that system and the databases at my work, I'm doing pretty darn well.

Here are just a few sources that are available through institutions or for personal subscription: JSTOR (which you all already know about); ProQuest Historical Newspapers; Proquest American Periodical Series; Newspaper Archive.com; Gale Group InfoTrac Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers; and Newsbank, including their Genealogy section that has scans of thousands of newspapers.

Which reminds me. A belated congratulations to good friend Mark, who recently passed his comprehensive exams at Ohio State and is now a Ph.D. candidate who needs to write his dissertation. Way to go Mark--now put those online resources to good use.

Speaking of Mark. The last three Netflix movies were United 93, The Family Stone, and the second Pirates of the Caribbean. Nothing to say about United 93, because it was just a reminder of all that once was, and all that should have been. Pirates of the Caribbean was what it was, only longer. Dear God, two and a half hours rambling about and they still didn't finish the damn story. At least they did their best to make Keira Knightley look like a boy, which works out well because Orlando Bloom looks like a girl. At the rate we are going, in ten years every movie and television show is going to feature a bunch of 105 lbs. hairless androgynes running around in smooth white unitards listening to weird techno music on their color coordinated MP3 players. Turn on your tv, the commercials are already in this bright future.

The Family Stone was a decent if slightly depressing Christmas movie starring Dermot Mulroney and Nelsonville's own Sarah Jessica Parker. The two standouts in the movie are Craig T. Nelson and Luke Wilson. Imagine it, Coach and Frank Vitchard, carrying the show. Two points about this one: first, I've never seen a movie check as many boxes in so short a time as the scene when son Thad Stone walks into the his parents' home. Within about five seconds we find out that Thad is deaf, Thad is gay, and Thad brought his longtime black partner home for the holidays. All Thad needed was a hard-working blind parapalegic Asian midget assistant with a hare lip and a spicy attitude.

Second, the plot revolves around the successful Mulroney bringing the successful Parker home to meet the family for the first time--the latter is hyper nervous and the former is trying to figure out whether he loves her and what he wants from life. Fine, but for one thing, in real life (and pretty much on screen) Mulroney is 43 and Parker is 41. Even if we are to assume they are in their thirties--even Christmas charity can't put those two in their twenties--what thirty year old successful people don't know how to handle themselves when meeting new people? I know some adults with some severe confidence issues, and even they have come up with mechanisms for dealing with challenging social interactions. It was like he was a teenager bringing his date to meet his parents before going out to the Homecoming Dance. You have to be remarkably shallow or incredibly stupid to be thirty something and be so lacking in self awareness and basic social skills.

But that is an indication of a growing Peter Pan mindset in this country. College students make no pretense at acting like they should be adults when they leave school, and video game companies target adults every bit as much as kids. My generation has avoided the Baby Boomer penchant for taking themselves way too seriously, but perhaps at the cost of not taking themselves seriously enough.

On a related note, the campaign to enjoy youth even when youth is over has led to a lot of older single people and couples choosing to put off marriage and having children until it is too late or almost so. I can't help but think of that when never-married forty year olds are acting like teenagers in movies like The Family Stone. Please, if you are older and single or older and do not have children, do not take offense at these comments, because none is meant. I understand that everyone has their own issues, their own reasons for making the choices they make. I just have trouble relating, especially to such movies, because I have made some very different choices, and I am reminded of the results of those choices, relentlessly--and, lucky for me, mostly happily.

Christmas in a new city. NB: I apologize that what follows is going to be the slideshow from hell, but, hey, it is my diary, after all.... (Mark well: NB stands for "nota bene," a Latin phrase used by pointy headed academics to tell people to pay attention to something, and I'm pretty much a pretentious jackass for using it in a blog diary post about taking the kids to into the city for Christmas. Just so you know.)

So we took the kids into the city for Christmas.

The focus of the trip was Kansas City's Union Station, which is connected to hotel/mall complex called Crown Center plaza. (And is across the street from an old World War I memorial and the brand new National World War I museum, about which I will have more at a later date.) The station and the plaza are literally connected--the enclosed walkway goes over a bridge and offers a nice view of the city:

I also took this picture from the walkway, which, if it were in Fargo or Minneapolis, James Lileks would tell you the building's whole history:

Oh hell, fine, I'll look it up, wait a second.... Here we go: Western Auto was a company started in 1909 by George Pepperdine, the guy who founded the university in California, and the building in KC was a headquarters, built in 1915. It started as the Coca Cola building, and obviously did not have the sign then.

Hold on... oh my, there's even a postcard:

Western Auto bought the building in 1951, and the current sign went up the next year. Western Auto put the building up for sale in 1999, and a few years ago it was converted into condominiums. They kept the sign, and I took the picture. Happy?

The same kind history, some real, some manufactured, is everywhere at Union Station, which is a grand edifice, the likes of which we do not seem inclined to build anymore. Here is a shot that unfortunately came out a bit blurry, but gives a sense of the scale of the place:

At one end, where people used to sit and wait for their trains, they've installed a diner to look like what it used to look like when people used to sit and wait for trains, only it didn't look like that. But it could have.

We found jolly Saint Nick, and, unlike the terrified child who preceded us in line, the boys performed with perfect aplomb in the face of the hefty red-clad hirsute elf.

Crown Center and Union Station, knowing how to draw crowds of frothing choo choo-obsessed 2-5 year olds, parents in tow, had about 650 different trains and train displays. A high school choir, boys in tuxes and girls in formal dresses, sang in the lobby, while we visited the displays of trains and gingerbread houses and trains and whole cities and trains and trees and lights and mirth and all that.

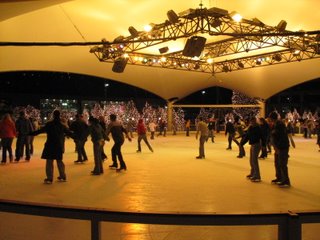

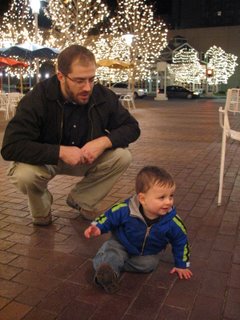

The last picture came from outside, and if the boy doesn't look cold, it's because he wasn't. Not at all. The warm weather robbed some of the Christmas atmosphere, but it sure made it easier to go outside with the kids, and take pictures of the ice skating rink and tree, fountain, and obligatory train.

It was so warm even that the younger boy decided to sit on the ground outside to get a little rest, and we didn't mind.

We didn't mind at all, this Christmas in one small part of our new city, a city every bit as nice this season as DC was last year. In some ways, the important ways, better, and not just because the boys made it so, but because the people in the city were better: friendly and polite in the stores, holding doors for each other, smiling as they circled the rink, free from the weight of the worries of the capital and the sad distrust for fellow man that hangs over the District.

Yet they call them rubes of flyover country, these people who live with the peace of a sense of common decency and joy for life. Call them rubes. Call us rubes, as long as ever it is so.

Merry Christmas.